Een nieuwe blik op de wereld

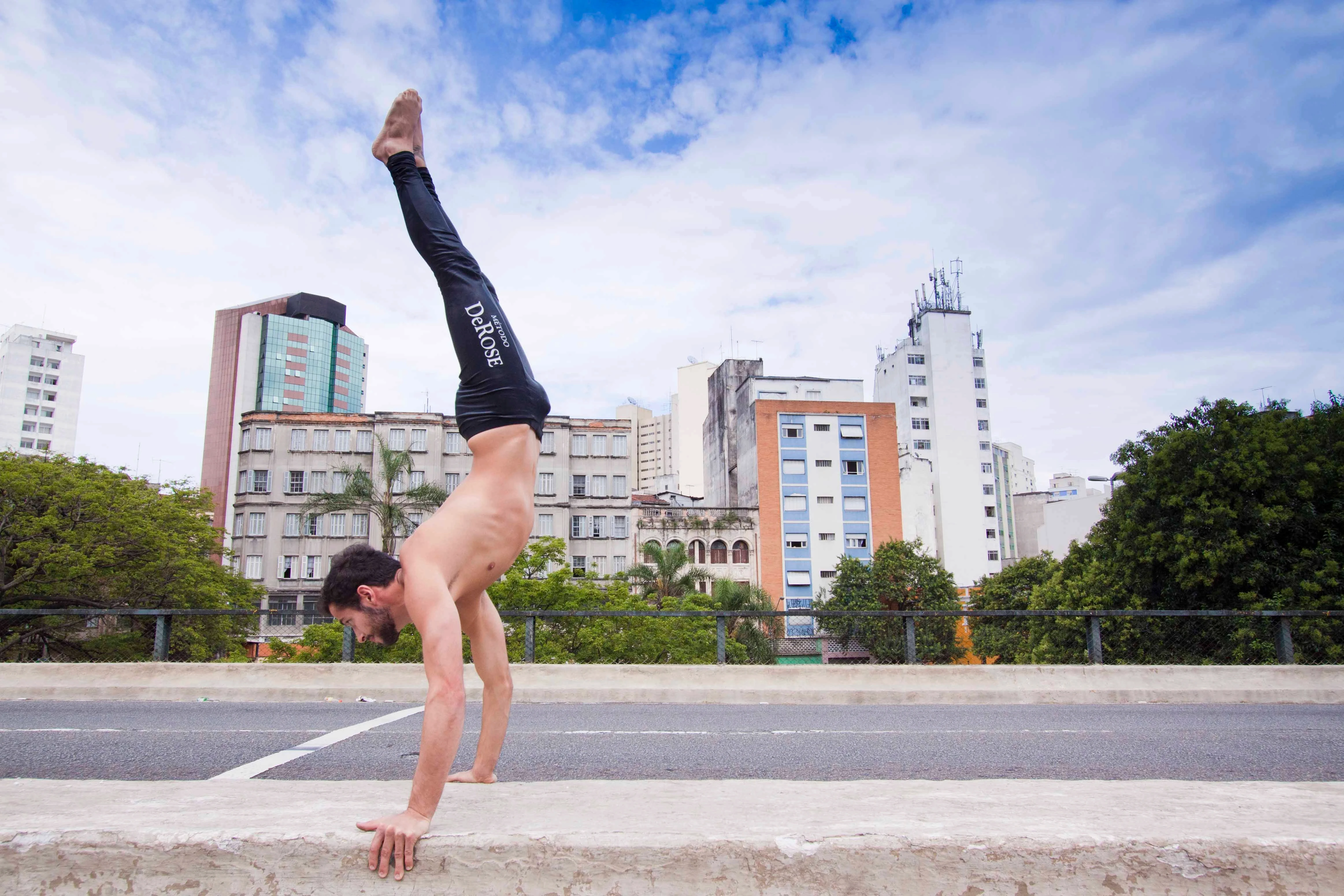

De DeRose Method verbetert levenskwaliteit door zelfkennis te verdiepen en focus & productiviteit te verhogen. De methode biedt technieken voor stressmanagement en emotionele beheersing, wat leidt tot meer veerkracht. Daarnaast stimuleert het persoonlijke groei en doelgerichtheid, terwijl de ondersteunende gemeenschap een gevoel van verbondenheid creëert. Deze elementen samen dragen bij aan een algehele verbetering van de levenskwaliteit.

Voor high-performers

Wij helpen de focus te verbeteren van atleten, ondernemers, executives, artiesten en andere ambitieuze toppresteerders. Bekijk hoe de DeRose Methode hun leven heeft beïnvloed.

Wat is de Derose Method?

Hoe de DeRose Method werkt

De DeRose Method heeft een specifiek doel: jouw leven verbeteren.

Wanneer wordt er les gegeven?

Over ons

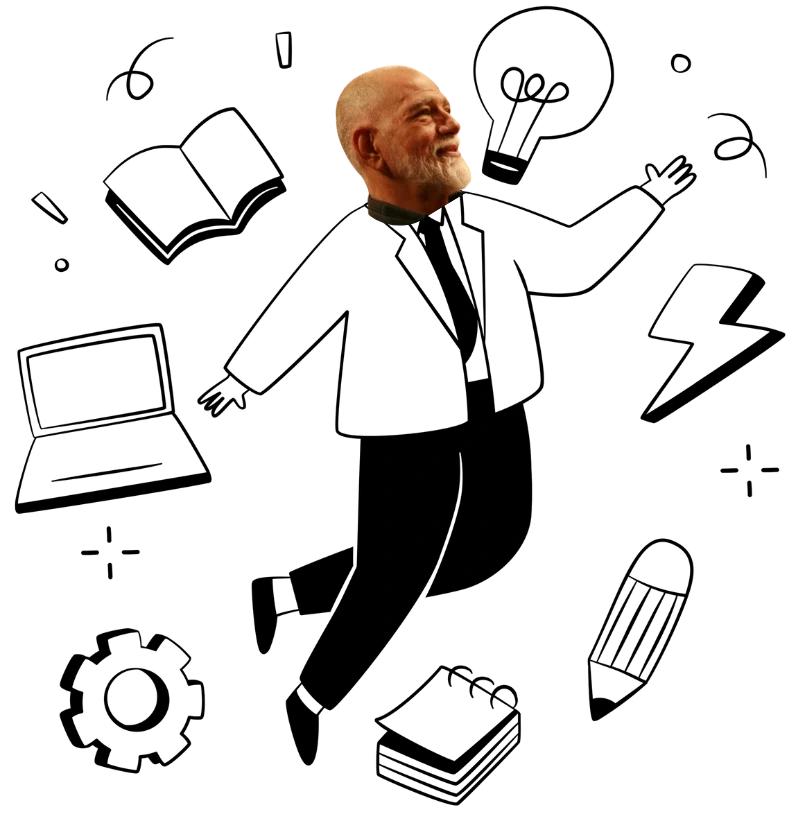

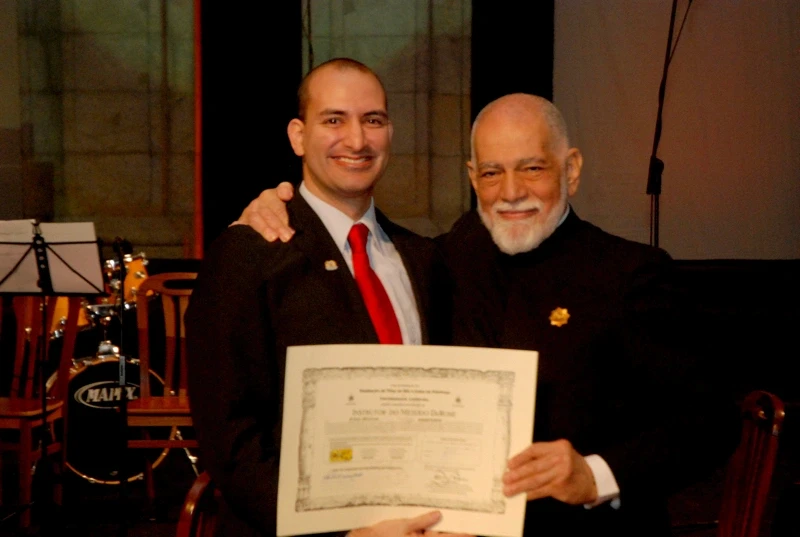

De DeRose Methode, opgericht in 1960 door de 16-jarige Professor DeRose in Brazilië, leert studenten hoe ze hun prestaties kunnen verbeteren en zichzelf beter kunnen kennen. De methode combineert fysieke technieken met concepten voor persoonlijke groei en is nu aanwezig in 12 landen.

Ons aanbod

Naast onze community van top performers, geven we dagelijks groepslessen & 1-1 trainingen. Wat is jouw welzijn waard voor jou? Wij bieden lidmaatschappen aan. Geen lessen.

Ontdek DeRose met Notion (Gratis)

Laten we eerlijk zijn, van alleen een webpagina met een beetje tekst kun je echt niet weten waar de DeRose Method over gaat. De DeRose Method gaat dieper. Je moet het ervaren.

Ga nu de diepte in met Notion door toegang te krijgen tot exclusieve content, zoals video-recordings en onze encyclopedie!

Jouw leraar

Our team of certified and experienced instructors brings a wealth of knowledge and a deep passion for yoga. Each instructor offers a unique teaching style, ensuring you find a class that resonates with you.

Lees over de DeRose Method

These articels are designed to capture attention and highlight the benefits, events, and developments related to yoga.

Wil je gezonder, positiever en langer leven?

Dat is al wat meer dan 20.000+ studenten ervaren wereldweid. Sinds 2020 ook beschikbaar in Nederland.

Contact Info

Locatie

Amsterdam, Online

Contact

Whatsapp : +31 6 27240542

Email : fabio.martins@derosemethod.org

Starten met de DeRose Method

Starten met de DeRose method betekent een stap zetten naar een gezonder, effectievere levensstijl.

Wij raden je aan om eerste onze Notion pagina te bekijken om kennis te maken met onze methode.